The only suggestion there is of any notable activity on this property before Clyde and Lucile Manley arrived in 1920 comes from a conversation I had with the owner of a local road grading company Quaker Center hired in 1986 to expand and level some of the roadside parking lots near the Orchard Lodge. During one of his work breaks he told me of his fascination with early maps of the area, one of which was on upper Hubbard Gulch Road. On this map there was a mark indicating the entrance to a gold mine. He had followed up this discovery with further investigation about the possibility of gold mining in the area and was told that two miners digging at the top of Hubbard Gulch Road had been either interrupted in their endeavors or threatened with discovery of their secret and had then quickly covered up the entrance to the mine. He said that for some unknown reason they were unable to return and, to this day, the entrance to the mine has been left undiscovered and undisturbed. He didn’t know whether the mine was on the Manley parcel, only that it was at the top of Hubbard Gulch Road. This possible solution to Quaker Center’s financial needs is likely to remain forever one of my favorite legends of the place.

Getting closer to what can be verified, we begin with a riddle: What does Quaker Center have in common with Isaac Newton and Steve Jobs? [Ans. The legends surrounding their early histories all started with an apple.] In Quaker Center’s case, it turns out that the first story we hear from a family member has Clyde Manley biting into an apple he picked up at a farmers’ market near Santa Cruz. It was so tasty he inquired of its provenance and learned it had come from an orchard up Hubbard Gulch in Ben Lomond. It turned out that a 50+ acre farm was available in that very gulch, and that this farm had apple trees. The rest is not legend, but history.

The approximately 51-acre rectangular parcel which forms most of the Quaker Center property on Hubbard Gulch Road in Ben Lomond was purchased by Clyde and Lucile Manley on February 25, 1920. The Manleys had given birth to one daughter, Virginia, and had adopted another, Eleanor, by the time they moved onto the parcel, which they referred to as “the Gulch”. Virginia Manley Rusinak recalled what it was like living on their Ben Lomond property in a letter of May 12, 1997 to the Quaker Center Association:

The approximately 51-acre rectangular parcel which forms most of the Quaker Center property on Hubbard Gulch Road in Ben Lomond was purchased by Clyde and Lucile Manley on February 25, 1920. The Manleys had given birth to one daughter, Virginia, and had adopted another, Eleanor, by the time they moved onto the parcel, which they referred to as “the Gulch”. Virginia Manley Rusinak recalled what it was like living on their Ben Lomond property in a letter of May 12, 1997 to the Quaker Center Association:

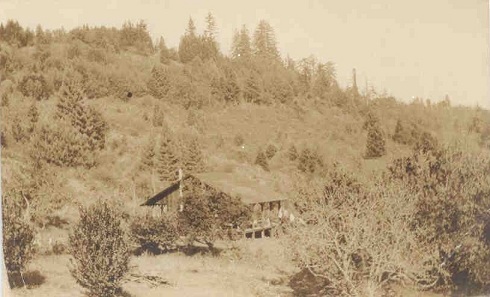

“It’s extraordinary that any part of the original house is still standing in spite of –in our day– termites in the walls and wood rats frolicking in the attic. (70 years ago)…there were only two small rooms with unenclosed porches on either side where we slept in the summer. The roof was supported by rough redwood posts with the bark still on them. There was no running water, and no electricity. We carried water, two pails at a time, from the stream ….

“There was a wonderful old two-story barn made of heavy redwood planks where the present garage now is, and an outhouse and stable on the other side of the big redwood tree. The house was surrounded by fruit trees: an apricot in front, an Oxheart Cherry next to the barn, a huge mulberry tree on one side, big enough to climb in, and over toward the orchard, lemon trees so tall, before they froze, it took a double-size ladder to harvest the fruit. Where the present orchard is, there were apple trees, peaches, plums, nectarines, cherries and grapevines. There was an extensive wine-grape vineyard over near the volleyball court area (Ed. Now the labyrinth)…. There was a Bellefleur and strawberry apple orchard on the steep hill which slopes down to the present Quaker Center entrance.

“…all the years my Dad spent working on the land, nurturing what was left of the forest, keeping the fire trails open (we sometimes saw smoke from forest fires just over the ridge), and trying to make a living from the orchards and from selling woodwardia ferns that grew along the streams…”

(Ed. More of Virginia Rusinak’s memories are on the video taken at the 50th anniversary celebration in 1999.)

In a conversation with me, Virginia described the way her father dealt with purifying the water which they carried from the holding tank that at some point had been installed in the creek. She said that he would simply lift the top off the tank and toss out any dead mice found floating on the surface of the water. She did not say whether or not they then boiled the water. After carrying water by hand throughout the early years, the Manleys eventually installed a water ram in Marshall Creek to pump water uphill to their house.

In a conversation with me, Virginia described the way her father dealt with purifying the water which they carried from the holding tank that at some point had been installed in the creek. She said that he would simply lift the top off the tank and toss out any dead mice found floating on the surface of the water. She did not say whether or not they then boiled the water. After carrying water by hand throughout the early years, the Manleys eventually installed a water ram in Marshall Creek to pump water uphill to their house.

Virginia had a collection of stereoscopic photos taken on their property, which she showed at Quaker Center more than once. In one of the photos, because the forest had been so heavily cut over the preceding years, the town of Ben Lomond is clearly visible from the porch of the Manley House, where a horse is tethered. This porch, now the library, was not enclosed and had no windows.

Little else is known about the Manleys during the years from 1920 to 1949 other than what Virginia relates in the above-cited letter. Some of their reasons for being here in the first place and why they found it so rewarding are revealed in a letter Lucile Manley wrote to Paul and Virginia Brink in 1967.

“We lived briefly in Berkeley, adopted a six-month old baby girl, and moved to Mount Hermon for her sake. Late in 1919 we came upon the fifty-acre tract up Hubbard Gulch near Ben Lomond which was for sale. It had no house, only a stable and “fruit house”. We fell in love with the beauty of the hills and forest….”

Later, and for much of the time between 1920 and his death, Clyde Manley, for reasons of health, lived alone on the property while his wife taught school in Hawaii in order to earn income for the family. Virginia Manley Rusinak writes of those years:

“My mother and I, and later an adopted sister, spent the school year in Honolulu where Mom taught in a public high school…. Each fall my Dad would ship us, by freighter, boxes of Ben Lomond apples. They didn’t last very long in tropical heat without refrigeration, but they filled the whole house with a delicious fragrance.”

The records of a handful of legal occurrences from those years are in the files. On October 14, 1931 the Manleys made the last payment on their mortgage. A few years later, on October 4, 1934, a transaction with later implications for Quaker Center took place: Clyde Manley sold for $10.00 an easement from Hubbard Gulch Road through his parcel to that of a small neighboring parcel of 3+ acres on the southeast corner. This easement, clearly visible on early parcel maps of the property, remained unused and that other parcel remained undeveloped during the entire time the Manleys lived here.

Lucile Manley had an unmarried sister, Edith Cold, who also moved onto the property at some time during their stay here. Miss Cold, as she was always called, hired a local carpenter, Joe Correia, to construct a small residence for her, which was known as the Cold House until it became the Sojourners’ Cottage in 1984. All that we know of Miss Cold is that she had been a missionary in Turkey for nearly 20 years. A newspaper interview tells of a trip she took there on horseback with her guide and interpreter. Along a narrow mountain trail the two of them were met by a band of local riders, whose leader announced to her: “Allah has decreed that you shall be my wife.” Edith Cold, who by that time must have acquired some experience and confidence with Islam and local customs, responded without hesitation: “Allah can also change the minds of men.” The leader was so impressed with this response that he remained silent and let them pass.

Miss Cold lived in the Manley House after her sister Lucile’s death in 1969 and until she herself needed more care in the mid-1970s. During those years, Joe Correia lived in her cottage, which was sometimes referred to as “Joe’s House”. Users of Quaker Center in the early 1970s were encouraged to respect Miss Cold’s privacy by not taking the short cut beside her house on their way from one part of the property to another. In 1980, Edith Cold, who had survived her sister Lucile, was still living in Santa Cruz, although not at Quaker Center, when she was visited on her 101st birthday by Dee Steele, the resident Program Director at that time.

Clyde Manley died in Ben Lomond on December 6, 1947. His widow was left to consider how to manage their 51 acres of hills and forest. Several handwritten letters from Lucile Manley to Stephen Thiermann, then Executive Secretary of the Northern California Regional Office (NCRO) of American Friends Service Committee in San Francisco, have been kept in the original AFSC files, now transferred to Quaker Center. In the first such letter, dated June 6, 1948, she writes:

“Dear Mr. Thiermann:

Nearly thirty years ago my late husband, Clyde W. Manley, and I purchased a fifty-acre tract of land in Hubbard Gulch, near Ben Lomond…

From the first we entertained vague hopes of devoting the land to some humanitarian project. However, to get the land paid for and to bring up and educate two children, I spent some twenty years as a high school teacher in Hawaii; the while my husband, too, was variously employed.

On Dec. 6. 1947, my husband was suddenly stricken, death due to heart failure. Since that tragedy occurred, I have been thinking deeply and prayerfully of the use these acres could be put to — some humanitarian project which might, in the end, be a memorial to my husband. Since he was for twenty-five years an elder in the Ben Lomond Presbyterian Church, I have thought more than once of writing the Presbyterian Board of National Missions, offering this tract to them. Yet I have not felt exactly led (Ed. Emphasis hers) to do so.

The tract is somewhat hilly, consisting of considerable redwood forest on the north side of the gulch, a level tract of perhaps seven acres under cultivation on the south side, and the rest, both level and hilly, overgrown in brush and scattered trees. Three streams converge in the deeper parts of the gulch, and several springs in higher areas supply water by gravity. Soil and climate too are favorable.

My own choice for the use of these acres would be to rehabilitate several homeless refugees of North Europe with a bent to agriculture. Even more appealing to me is the idea of providing a home for orphan children — German or Austrian.

I have some realization of the tremendous implications to myself, should the Friends develop a project here. Since God is unhurried in the working out of His plans, I am also prepared for much deliberation on the part of your board, and of course answers to many questions, as well as personal surveys of the tract in question should the Friends be interested in accepting these acres.

Very sincerely yours,

Mrs. Lucile Manley”

Some months later, after having met Friends from AFSC, she writes: “It does no harm for me to dream of participating some day in a project involving displaced persons or war orphans, but I am under no illusions as to the practicability of making use of this tract of land…. In closing…I need to say that it was indeed a pleasure to make the acquaintance of persons having a quality different from the average ‘Christian'”.

[Lucile Manley to Stephen Thiermann, November 14, 1948]

Lucile’s attraction to the Quakers was strengthened by her brother-in-law John Manley (World Secretary of the YMCA at some point during the 20th century), who had written to her that “The Quakers would be a fine organization to carry out welfare plans involving your place. I have great admiration for the Friends organization and know some of their national leaders.”

[Lucile Manley to Stephen Thiermann, January 12, 1949]

Lucile Manley goes on in this same letter, expanding on her earlier thoughts, to wonder whether AFSC workers in Europe might find a displaced family who could be housed on her property in an agriculturally self-sustaining manner, and whether AFSC might construct tent platforms and other modest facilities for camps, retreats and other similar projects.

The national office of AFSC had clear reservations about the idea:

“Contributions of this kind are usually of doubtful value and we have to repeatedly turn down offers, because they would be too expensive to operate in order to fulfill the wishes of the donor…. it sounds to me of doubtful value under the conditions, unless the land could be disposed of and the money used in a way that would be acceptable to both the donor and the committee.”

[Homer L. Morris, Philadelphia AFSC staff, to Stephen Thiermann, August 9, 1948]

Our files have no record of whatever Quaker good order the NCRO used to either reject or ignore this advice from the national office, nor of how these two branches of AFSC came to unity sometime in early 1949 and agreed to accept Lucile Manley’s offer.

Next section: 1949-1959 >

< Return to section: Introduction