In 1947, the British Friends Service Council and the American Friends Service Committee jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of 300 years of Quaker action directed at healing rifts and opposing war. In particular the Nobel Committee named the work done by the two recipient Quaker organizations during and after the two world wars to feed starving children and help Europe rebuild itself.

The work done by Friends among those affected by the wars sounds a lot like what Lucile Manley wanted to do for them by using her property near Ben Lomond. We do not know if she was directly inspired by the Nobel Committee’s choice in 1947, but we do know that two years later, she had chosen the Northern California Regional Office of AFSC to be the recipient of her own prize, the 50 or so acres that would later be named Quaker Center.

Perhaps the first official notice of the existence of what is now Quaker Center came at the 3rd annual session of Pacific Yearly Meeting (PYM) and the 17th annual session of the Pacific Coast Association of Friends (now College Park Quarterly Meeting = CPQM), held together in Pasadena from August 11-14, 1949. From its minutes:

“Vern James reported that Mrs. Manley of Santa Cruz had donated to the AFSC her 50-acre property located near Santa Cruz. As the AFSC is not yet incorporated in California, title of the property is being held by the College Park Association for the time being. The property is administered by a Committee of Three: one representative from AFSC, Northern California Regional Office (NCRO), one representative of PYM, and one from California Yearly Meeting (programmed Friends) ….The Meeting instructed the Clerk to write a letter of appreciation to Mrs. Manley.”

The identities of the three administrative committee members were not given.

It seems that discussion of how Friends might use the Manley gift had begun some time earlier, as noted in a letter of April 19, 1949 from Stephen Thiermann: “The AFSC has been discussing appropriate uses of the property for approximately one year with Mrs. Manley.” Mrs. Manley herself, learning of the need for some definitive word on the subject, sent the following brief telegram to Vern James on April 17, 1949: “Offer land for interracial camp managed by Friends”.

And just a few days later, in a memo dated April 21, 1949, Stephen Thiermann says: “…we have concluded that probably we should go ahead with the establishment of a summer camp with groups representing different races in attendance…. (W)e have been granted an attractive 50-acre site in the Santa Cruz mountains….The property… has one very large home, which would be ideal for conferences and retreats, and another smaller home which would be quite satisfactory for a caretaker.”

Since the only home on the property was the Manley residence, now the Quaker Center Office, its description as a “very large home” seems an embellishment on Quaker plain speech. Throughout the rest of the century, Virginia Rusinak, the daughter of Lucile Manley, would apologize for this house whenever she visited the property and wonder why it had not been torn down. In any case, whatever one thought of it, the use of the house at that time “for conferences and retreats” could not have been possible, since it was to remain as Lucile Manley’s residence until her death.

Among the first activities held on the property under the auspices of Friends was a memorial service for Clyde W. Manley on July 17, 1949 in what was then called “the Cathedral” on the Ben Lomond property. (Ed: this is presumed to be what is now either Redwood Circle or Quaker Circle. Quaker Circle seems more likely to the author since it is known that Lucile Manley’s ashes are buried there. Also, what is now the Redwood Circle was at that time the boys’ camp ball field). At the time of the memorial, the proposed interracial boys camp at Quaker Center had already been started under the leadership of Josephine Duveneck (of Palo Alto Friends Meeting and Hidden Villa near Los Altos). The campers were invited to the service: “The service…would afford an opportunity for building a bridge between the interracial campers and the citizens of the Ben Lomond area.” [Stephen Thiermann to Lucile Manley -7/3/49]

The camp actually preceded the signing of the deed granting the property to Friends, as we learn later that summer: “I wish that you, Mr. Jones, and I might draw up the Gift Deed at a time when camp is not in progress. The first campers left for home today after two weeks of camp, and on Monday twelve new ones arrive.”

[Lucile Manley to Herbert C. Jones – July 22, 1949]

The relevant text of the original grant deed, mentioned by Lucile Manley in the preceding letter and dated August 10, 1949, is:

“LUCILE MANLEY, a widow, grantor, and THE COLLEGE PARK ASSOCIATION OF FRIENDS, a religious corporation organized under the laws of California, grantee, WITNESSETH:

That said grantor and her deceased husband, Clyde W. Manley, for many years have cherished the purpose that their property of approximately 51 acres near Ben Lomond, California, and hereinafter described, which had been their home for the greater part of their married life, should be conveyed by them to a suitable charitable or religious organization, to be perpetually dedicated and used for summer camps, conference grounds, and other purposes for the enjoyment, betterment, education, and welfare of mankind , and

WHEREAS, the policies, principles, activities and work of the Society of Friends (commonly called Quakers) appealed to said grantor and her husband as embodying the purpose to which said grantor and her husband desired to have said property permanently devoted;

NOW, THEREFORE, the said Lucile Manley, grantor herein, does hereby grant and convey unto said corporation, THE COLLEGE PARK ASSOCIATION OF FRIENDS, all that certain property situated in the County of Santa Cruz, State of California, described as follows: …”

The deed reserved a life estate to Lucile Manley and to her sister Edith Cold under which they retained the use of the Manley House and the Cold House together with the land “within the deer fence”.

Herbert C. Jones, who helped Mrs. Manley with the draft of the deed, was an attorney and a Friend in the San Jose Meeting who was elected to the State Senate in 1913 at the age of 33. His mother had been one of the 8 charter members of the Sempervirens Club formed in 1900 to “save the Redwoods.” One of the first acts of the Sempervirens Club was the introduction into the 1901 state legislature of a request for state appropriation of $250,000 to purchase 2500 acres which became California’s first state park – Big Basin – 10 miles or so north of Ben Lomond. The desire for preservation of forested properties such as Quaker Center must have been impressed upon Herbert Jones from his early years, for he remained one of the key figures in the beginnings of Quaker Center, his name appearing numerous times in letters, minutes and reports throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s.

Lucile Manley, exercising her life estate just a few yards away from the campers during that first summer of 1949, obviously could not stay uninvolved. She writes: “While I am not officially on the staff’ I do, as you can imagine, fill in, in a hundred ways, to keep the machinery going.” The “hundred ways” she refers to, and the nature of the camp itself, are spelled out as she goes on:

“Since I had the ‘honor’ of supervising dishwashing, I learned in conversation with individual boys many things about their background … and reactions to this camp…. a few of the things they said to me:

‘I like this camp better than any other because of the few boys so that it seems just like one large family.’

‘I think it is good to help with work projects.’

‘In this camp you are allowed to tell what you like to do, and help plan the program.'”

Mrs. Manley says about the program: “(It) included two or three hours of …work projects mornings, a period of rest and relaxation after lunch, recreation of some sort in the afternoon, and entertainment or camp fire in the evening….Conduct of morning devotions…followed by a few minutes of ‘Quaker silence’.”

[Lucile Manley to Herbert C Jones, 8/24/49]

The first meeting of the group appointed by AFSC to manage the activities on the property occurred on Nov. 12, 1949, with Vern James as clerk, and Josephine Duveneck, Fred Fellow, Herbert Jones, and Otha Thomas in attendance. The first name for the property is chosen to be Ben Lomond Camp, and the group chooses for itself the name Ben Lomond Committee (BLC). The status of the BLC was to be comparable to other AFSC Regional Office social, industrial, peace education and foreign service committees, namely policy-making, with decisions subject to review by the Executive Committee (Exec C) of AFSC. Some of the topics discussed at this first committee meeting were: San Jose Monthly Meeting was recommended as the caretaker of the property, and was asked to name an individual who would oversee this, for a term of six months initially; a publicity brochure was to be planned and printed; a telephone to be placed on the property; stationery purchased; liability insurance secured through AFSC; and some accounting for the apple crop (the need for which was to not repeat the wastage of the current year’s crop). Apparently, the previous summer’s camp had used Mrs. Manley’s kitchen to prepare their meals, because the committee suggested funds were needed for a kitchen and dining room, so that hers would not be abused. A second camp for the following summer was recommended under those conditions.

At only the second meeting of the BLC on 12/13/49, we learn that there are already concerns to deal with: a neighbor is cutting trees on the property; a person named Paul Mallette wants to construct a small private dwelling (he is to be given a negative response because of uncertainty about future development of the tract). To manage these and other concerns, Herbert Kreinkamp, an architect and member of the San Jose Meeting, is given the responsibility of supervisor of the property for the next six months, from January 1 to June 30, 1950.

Although the Manley parcel was given to the College Park Association of Friends, it was clear from the beginning that this was not to be permanent. Within a year, the title to the property was transferred to the San Francisco regional office of the AFSC. Notification of this transfer is recorded in a letter of April 1, 1950 to William James from Herbert C. Jones:

“At the coming Quarterly Meeting on May 6th, I will present a resolution authorizing the execution of a deed of the Ben Lomond property from the College Park Association of Friends to AFSC. The articles of incorporation for AFSC have now been filed in Santa Cruz County so that the property now no longer need be temporarily held in the name of the College Park Association of Friends.”

While the boys’ camp took place on the part of the property east of the Manley residence, the area of the current Redwood Lodge, they did use a “ball field” in what is now the Redwood Circle. Early in 1950 Friends received a request for another use on this upper part of the property. This came to the BLC from Harry Rathbun, leader of an organization doing business as Sequoia Seminar, and specified: in lieu of rent, to have use of the Ben Lomond property and to construct buildings over perhaps a five-year period. The receipt of this proposal indicated to the BLC the need for an overall plan in the long-range development of the Ben Lomond property. Specifically, the need for separation of the Sequoia Seminar and the boys camp became immediately apparent. The proposed size by Sequoia for their assembly hall – 30 persons – was at first questioned by Friends because of their own initial thought of using the property for Quarterly or Yearly Meeting, and that perhaps the assembly hall should accommodate 100 people. Obviously, this suggestion did not prevail, because the assembly hall Sequoia built is now the Casa de Luz.

The early leaders of Sequoia Seminar were at first members of the Palo Alto Meeting. Harry and Emelia Rathbun joined that Meeting in 1951, but left two years later. Leon and Lucille Carley joined in 1952 and left 8 years later. Their membership may have led to their hearing of the existence of the Ben Lomond property and their subsequent asking Friends about using it. They may also have heard of it from Vern James, one of the most active members of the BLC during the 1950s and 1960s, who had taken Sequoia’s course in the sayings of Jesus. The author of this course, Henry Burton Sharman, also had some connection to Friends because he had taught the course at Pendle Hill some 15 years earlier. Because of such connections, the Sequoia request must have seemed like a good fit for use of the property.

Sequoia Seminar quickly began to become more prominent in the minutes of various committees. From the AFSC Executive Committee on 1/14/50: “Vern James reported on his conference with Harry Rathbun. The Rathbun group is interested in the possibility of financing the construction of an assembly hall, dining room and kitchen on the Ben Lomond property…. (T)he Rathbuns would hope to conduct seminars of not more than 30 students each and varying in periods of time but using the buildings continuously from June 1 through September 15.” Agreement to proceed was given by the Executive Committee at its meeting of 3/11/50.

Harry Rathbun explains how all this came to be in a letter written to Lucile Manley some years later: “The seminar had been the beneficiary of a gift of $10,000 and we saw this as perhaps making possible a substantial beginning of the development at Ben Lomond of facilities for the joint use of the Friends and the Seminar for their common purposes: the Friends to provide the land and we to provide the buildings. This seemed a particularly happy idea in view of the fact that the Friends had no money for building and we had no money for land.”

The first legal agreement between the two parties was dated 4/30/50, and signed by Vern James and Stephen Thiermann for Friends; by Harry Rathbun and Leon Carley for Sequoia Seminar. The agreement ended by stating that “it is the hope and expectation of the parties that it will continue in effect so long as the parties continue to function with mutually congenial objectives and methods.” Either party could terminate the agreement with one year’s notice, but if Friends did so before 12/31/65, they would have to reimburse Sequoia for the value of their buildings, amortized over 15 years. Friends owned the buildings, as well as the land, and were responsible for their upkeep, and for half of all utility charges and insurance. Although there is no mention of this in the 1950 agreement, from other notes it is apparent that AFSC paid half the salary of a resident caretaker during most of the life of this agreement.

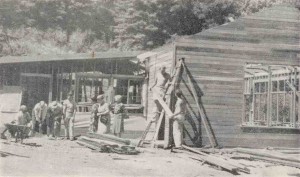

In the first year under the agreement, Sequoia built the (now Orchard Lodge) Dining Hall, supplying 70% of the labor, and 90% of the cost. The balance was supplied by Friends. The architect was Herbert Kreincamp of the San Jose Meeting. The Casa de Luz, called Main Lodge by Sequoia, was built in 1951; the caretaker’s house (now our Maintenance Manager’s), the nearby shop, and the warehouse (now our Haven) in 1955. According to Sequoia’s records, their out-of-pocket costs for all of the above, plus road improvements, were $40,464.

Quickly underway, the carrying out of this planned use by Sequoia is described in an article in the San Jose Mercury News of August 6, 1950:

“In a setting of unsurpassed natural beauty not far from here two idealistic groups are engaged in an unusual venture in cooperative working and living….

At Stanford University, Henry J. Rathbun, Professor of Law, heads an informal discussion group known as Sequoia Seminar….The seminar members…heard about the Friends’ camp and approached them with a proposition….. In return for 15 years’ free tenancy of the site, the seminar offered to build three buildings which also could be used by the Friends and other groups under its aegis. So, under construction now are an assembly hall, a dining room, and a dormitory (Ed. now on the Sequoia property)…. The seminar had $15,000 on hand, (and) …volunteer work on the part of seminar members, camp boys and friends of both are speeding the projects right along…. Material has also been donated…”

In their brochure announcing the first seminar at Ben Lomond, Sequoia says about living arrangements: “The seminars are held at a forest camp … (which) includes 63 acres of land in process of development by the Sequoia Seminar Foundation and the AFSC. (Ed. The 63 acres are comprised by the Manley parcel plus about 12 adjacent acres to the northwest purchased by Sequoia.) Meetings are held in a newly-built seminar lodge of striking design which commands an inspiring view of mountains and wooded canyon….Meals are served in a dining hall below the seminar lodge and living area.”

Meanwhile, simultaneous to the Sequoia construction, plans for the boys’ camp kitchen/dining room were presented at the 3/8/50 meeting of the BLC. The site of the structure referred to in these plans, and that was built that first year, was in the location of the present Redwood Lodge kitchen, and in essence became what used to be the former Hostel kitchen. A special grant of $1000 toward the development of the boys’ camp was received that year from the Columbia Foundation.

The boys’ camp was the only activity conducted on the property during the 1950s which was in any way managed by Friends, and this was only in a fairly remote manner. The original name for the camp was given as simply “Ben Lomond Camp”, for boys between the ages of 13-17, on a 1950 brochure stating that the camp was owned by AFSC and operated by Friends of Northern California. The committee in charge of the camp consisted of Josephine Duveneck, Fred Fellow, Vern James, Herbert C. Jones, and Otha Thomas. Among other specific items on its brochure wish list, the Camp asked for “camperships for Desirable Boys ($40 for 2 weeks)”

The brochure states that at that time, there were “outdoor washrooms with hot showers, toilet, septic tank and two tent platforms. A play site was cleared…. The camp will be repeated this summer (1950) if funds are available to carry on the program.”

Sometime early in its tenure at Ben Lomond the name of the camp became Camp Unalayee. One of their early brochures says this name is a Cherokee word meaning “Place of Friends”. In the concrete slab behind the previous Hostel kitchen, unfortunately not preserved in the Redwood Lodge renovation of 2004, appeared the words “Camp Unalayee 1954”.

On an early Camp Unalayee flyer, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Duveneck and Dr. Harry Rathbun are listed as sponsors. Josephine Duveneck states there: “Camp Unalayee is an outgrowth of a project originally sponsored by the AFSC.”

Other details of the early history of Camp Unalayee during their first decade at Quaker Center are given in one of their later brochures:

“A small camp for boys was established in 1949 by the AFSC near Ben Lomond, California. Its operation was carried along from summer to summer, but development was negligible until 1954 when…the camp received its names and the inspired leadership which has carried Camp Unalayee from its meager beginning to an operation serving more than 150 children each summer…. 1957 saw the first of the girls’ camp sessions…. 1959 brought the culmination of an 18-month search…. when Camp Unalayee bought a 600-acre property (in the Trinity Alps of Northern California).

Other than the boys’ camp, little remains in the files of any specific activities of Friends on the property during the 1950s. Lucile Manley and her sister Edith Cold continued to live there, exercising their life estate, for the next two decades. There are no minutes of the Ben Lomond Committee that remain in the Quaker Center files for the years 1951 -1961. When reference is made to what is now Quaker Center in letters and notes until about the middle 1960s, it is almost always called “Ben Lomond”.

We are left to wonder whether Friends, during these early years, ever worked toward some specific use of their Ben Lomond property for and by themselves. It seems there was doubt about anything at all, at least from the following assessment in 1952:

“Re the Ben Lomond property: … After seeing the situation and observing the numerous problems which must be solved in development of the site, we concurred with the opinion of the AFSC staff that the property probably should not have been accepted in the first place. We feel that much money must be spent upon the property before it can be of much service to the Friends. In view of the other projects being carried on by AFSC, we doubt whether this project rates so much expenditure at this time.”

[Ruth B. Woodard (Quarterly Meeting peace committee) to Stephen Thiermann]

In retrospect, this must have been a minority view, because at least Herbert Jones continued to show strong interest in the property. He made a request for $32,500 from the Fleischmann Foundation of Nevada on 6/12/52 to construct and equip a dormitory building on the Ben Lomond conference grounds. It is not recorded whether this grant was received. In any case, Friends did not build anything here on their own until the late 1960s. Herbert Jones shares his views with the AFSC Executive Committee in a note a year later (6/13/1953):

“Friends have been criticized (by their own members) for their ‘fetish’ against proselytizing. We can at least, however, expose young people and others to the great principles of Quakerism. In such a program, Ben Lomond could be a vital factor. By the construction of a combined dormitory and assembly hall the grounds would be equipped for just such conferences…. The grounds furnish the complete isolation and quietude desired for discussions, thought, and meditation. If we do not preserve Ben Lomond as a Quaker retreat, within the next 25 years people will indict Friends of this day for their lack of foresight. We have at Ben Lomond a truly priceless opportunity….The full use of the property requires two things: (1) Supervision; (2) Financial support. Neither of these requirements will come by just letting the property take care of itself. We need a definite program. Not to furnish it seems like defeatism. Nothing worthwhile in connection with Ben Lomond can be attained without a program and a determination. To neglect Ben Lomond, to possibly allow the property to be transferred to some other and transitory group, is not keeping faith with Mrs. Manley. It is not living up to the expanding and enduring possibilities of this project. I would reverently hope that the Executive Committee will continue with Ben Lomond.”

The tone of this note, and in particular its last sentence, suggests that at least some at AFSC may have been hesitant in proceeding in the directions advocated therein. Some proposals had in fact been circulated. A Ben Lomond Advisory Committee (listed members are : Fred Fellows, Josephine Duveneck, Vern James, and Otha Thomas) made a report to the AFSC Executive Committee, likely written in 1953 and entitled: BEN LOMOND PROPERTY EVALUATION MATERIAL. The report begins: “Is the need for this program increasing or decreasing at the present time? Should there be a terminal date set for the program beyond which it would not be continued without major consideration? If so, when would this date be?” The report goes on to list some potential programs: (1) a Pendle Hill of the west; (2) a retreat center; (3) a Friends secondary school; (4) California Yearly Meeting (programmed Friends) theological school; (5) a site for labor relations and other special group seminars. The report denied that it could be used for Pacific Yearly Meeting. It suggests a 5-year trial period, from 1953 to 1958, to be reviewed annually. A section headed “Concern” asks: “Is there a broad base of concern among Friends or among AFSC constituency for this program? Is it based on traditional Friends testimony?” and goes on to give its own answer to this question: “There is not a broad base of concern for either the potential or immediate uses of the Ben Lomond Property, but there is relatively strong interest on the part of a number of experienced Friends, including the following: Josephine and Frank Duveneck, Fred Fellow, Vern James, Herbert Jones, Dorothy Murray, Harry Cox, Herbert Kreinkamp, and Lucile Manley. These Friends, however, already have numerous other demands on them and may not have the time available which development of the property requires.”

The Executive Committee responded that the future of Ben Lomond depends upon “discovering a nucleus of Friends who are not only interested but free to spend time and energy on the proposed development.” The Committee went on to say that it “agreed that the Ben Lomond property was not a suitable site for a Pendle Hill of the west, Friends secondary school, or California Yearly Meeting theological school….”

In the end, Herbert Jones asked to “see what the recommendation of our College Park Quarterly Meeting should be as to how best to find, or set up, the necessary group to administer the Ben Lomond Project….”

It is not clear what actually happened with this or any other proposal from those years, for certainly the dormitory, assembly hall and children’s center mentioned therein were not built within the 5-year trial period ending in 1958. There are also no records from extant AFSC minutes about any of this plan being brought beyond the proposal stage.

One other proposal surfaces in correspondence during the 1950s suggesting that the security of at least some of the property in the hands of Friends may not have been as firm as written in the deed.

“Your letter to Mr. Jones, requesting that the deed of the Ben Lomond property from yourself be revised so as to provide that your home and the level land in front of it should be available not only for the lives of yourself, your sister (and your husband in case you should remarry), but now should be available for the life of your daughter, was duly received. Such a change would have the effect of postponing for an entire generation – possibly 30 or 35 years – the time when the Quakers could develop your home and the level land for such headquarters or institution as they might now plan on.”

[Albert T. Henley to Lucile Manley, 8/23/54]

There is no evidence that this proposal for a change in the Manley life estate was pursued to any degree by either party.

In any case, regardless of what Friends or Mrs. Manley might be proposing, only Camp Unalayee and Sequoia Seminar made any use of the Ben Lomond property throughout the entire decade of the 1950s. Though specific uses by Friends had been proposed, as in the preceding paragraphs, no concrete decision about any such use appears in available records from that time. One of the two users of the property filled this apparent vacuum with its own ideas and proposals.

In 1955, ten years before the agreement of 1950 was to end, a Memorandum of Essential Elements of Lease was drawn up and submitted by Sequoia Seminar. The opening paragraph states that Sequoia is “desirous of establishing a permanent location for the conduct of seminars…” Here, the original lease was to be extended until the end of 1990, and would include all 50 acres of the Manley property. It could be renewed at the end of this period for ten successive periods of 35 years each. (Ed. i.e. apparently until the year 2340 A.D.) The only contingency seemed to be that the lease could be terminated by AFSC if Sequoia did not use the property for 14 continuous months. If AFSC wanted to develop a program there, they would be able to do so on the portion east of the Manley life estate. No signatures appear on this memorandum, and there is no evidence that it was ever put into effect. It seems to stem from Sequoia’s perception of itself as the only ones making consistent use of the property in the manner that Lucile Manley had intended at its 1949 transfer.

At the end of 1955, Sequoia gives the impression that their intentions seem to have met some positive response, for they express quite boldly: “We understand that it has been agreed in principle that the seminar might have the exclusive use of the upper portion of the grounds so long as the seminar should carry on its program…. (W)e see no reason for complicating the running machinery by requiring approval of structures built on the upper grounds….If the seminar is to take full responsibility for the entire grounds, we think that we should say who shall use the grounds.” [Leon Carley to Vern James, 12/5/55]

It is clear now that this suggested full use by Sequoia did not take place in anywhere near this fashion. Rather, in the minutes of the AFSC Executive Committee (10/21/57) we read: “Reasons prompting the proposed new lease are Sequoia’s desire to maintain possession of the lodge and dining hall after 1965 for 95 additional years, and the AFSC’s desire to be relieved of maintenance costs through 1965 in light of the fact that AFSC has no present use for the property except as a site for a summer interracial camp…. (T)he committee decided any extension of the lease beyond 1965 was unwarranted, and referred the matter back to the Ad Hoc committee with a recommendation that it explore a plan of sale under which the dining hall, lodge, caretaker’s quarters, miscellaneous dwellings, and contiguous land would be conveyed to Sequoia for a reasonable sum.”

The forthrightness of Sequoia Seminar in expressing their intentions is somewhat justified as one is left to wonder how much the presence of Friends had been felt even by Lucile Manley, who writes to Stephen Thiermann (11/3/57): “I keep wishing that Friends, themselves, would make greater use of these facilities.”

By 1958, the vision of Sequoia regarding the property is quite clear yet somewhat different than what is stated in preceding paragraphs. “According to my recollection it is now about three years since the suggestion was made that it might be to the advantage of everyone concerned for the seminar to take over the entire operation of the Ben Lomond property….While we thought that such a plan on a lease basis had been worked out with the ad hoc committee of the AFSC, such informal information as we have received indicates that suggestions to date have not been satisfactory to the executive committee….Seminar planning will continue on the basis of the existing understanding providing for joint use of the property with the expectation that such use shall continue so long as the purposes of the two organizations are mutually congenial….If the AFSC should wish to think in terms of a sale with the consent of Mrs. Manley on terms that the seminar could handle, that would be considered also.”

[Leon C. to Allen Longshore, AFSC Executive Committee clerk, 4/5/58]

The suggestion in the previous letter of a “sale with the consent of Mrs. Manley” may have arisen because of a sense that the Ben Lomond property was causing AFSC some financial difficulty. From its records, AFSC had a net loss of only some few hundreds of dollars a year from 1949 to 1953. A budget a few years later proposes construction (with donated labor) of a dormitory, assembly room and children’s center with estimated total cost to AFSC over the 5 year trial period (1953 – 1958) of $33,575, for both capital and operating expenses. Income to AFSC from uses of the Ben Lomond property would not cover these costs. These buildings were not constructed, but the implication is clear that doing something here would require a financial investment.

There are other hints of doubt, at least in the mind of Lucile Manley, about Friends’ ability to manage the property financially: “Russ Jorgensen called to my attention the note he recently received from you in which there seemed to be an implication that the AFSC has suffered a financial handicap in consequence of our administration of the Ben Lomond property. To relieve any uncertainties in your mind, if they exist, I do want to write that our Finance Committee believes that the Ben Lomond property is a good financial commitment….Of course, the financial considerations are secondary to the much more important potential value the property holds for program purposes and services to human beings.”

[Stephen Thiermann to Lucile Manley – 12/30/58]

Over the first decade of its ownership, AFSC finance records show that the total income it received in connection with the Ben Lomond property was $8566.30 and the total expenses $14,335.21, resulting in a net loss of $5768.91. AFSC projected its net loss over the life of the first 15 year lease to Sequoia Seminar would be an additional $11,200.

AFSC’s deficit may have partially resulted from its decision, in effect from the beginning of its ownership of the property, to pay the property taxes resulting from its conscientious objection to signing the loyalty oath required to earn an exemption. On the Affidavit For Welfare Exemption filed by AFSC on 3/25/54 and signed by Stephen Thiermann, someone has stricken out the words: “That the organization does not advocate the overthrow of the Government of the United States or of the State of California by force or violence or other unlawful means nor advocate the support of a foreign government against the United States in event of hostilities.” Because this clause was stricken, an exemption was not granted.

Motivated by its refusal to sign an oath, the payment of property taxes by AFSC continued until 1958, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that the California property tax loyalty declaration was a violation of due process. It is possible that the subsequent tax relief may have led AFSC to feel more secure in its ability to hold the property without financial loss.

During these years, Lucile Manley faithfully reimbursed AFSC each year for what she considered her share of the property taxes stemming from her life estate. She is aware that it is costing AFSC something to hold the property, and she is led to consider easing this burden by imagining other ownership arrangements for the property, including suggesting a possible sale of at least the upper third of the property to Sequoia Seminar, the proceeds from which would help AFSC recover its costs.

While various negotiations back and forth with Sequoia continued throughout the late 1950s, some of which seemed to include Lucile Manley, the other user of the property had apparently begun to affect her differently. Rather than taking part in the camp as she had in its early years, she seemed troubled by being surrounded by dozens of boys for three months in the summer, so that by the end of the camp in 1957 she writes:

“The plain fact is that I was near to nervous exhaustion with the eight weeks of Unalayee Camps. Numbers have increased to the extent of 60 persons in the first session, and no doubt for those following, since 150 campers call for many counselors. The success of these camps depends to a large extent upon noise….From seven in the morning until ten at night is fifteen hours of continuous activity….Can we leave this situation in the hands of the Lord?….there are two sides to every question and the Spirit must guide.”

[Lucile Manley to Stephen Thiermann- 9/6/57]

In his later notes to the Files, written 10/4/57, Stephen Thiermann says: “Concerning Camp Unalayee, (Mrs. Manley) said that the noise persisted some nights until 1a.m. and that on several occasions she had to phone (the camp director) to ask him to respect her need for sleep and other neighbors in the Gulch. Noise was not made by the boys but by the counselors…She feels (they have) left her with unpaid long distance phone bills, never thanked her for the use of the property, declined to share the cost of maintaining the new roof on the water supply Camp Unalayee uses, and failed to compensate her for damage to her garage in a truck accident. Her net conclusion is that Camp Unalayee ought to move to a new site, two of which she said had been offered to Bruce.”

Mrs. Manley explicitly requested that the camp find a new site by 1959. She referred to it being too large for the property. She was also concerned about their cutting wood, dogs, and a burro which attracted flies and made noise.

Besides Sequoia Seminar and Camp Unalayee on the property, Quaker Center has over the years felt the presence of some half-dozen or so neighbors along Hubbard Gulch Road. To give the flavor of some of this impact, here are a handful of instances that surface in minutes and letters from that time.

In 1951, there was a dispute about water use. Applications for a change in use by Bennett, Correia, Emminger and Selyer were protested in a legal document by Sequoia, AFSC, and Mrs. Manley.

Edward Sylvanus wanted to do road work on his property above Quaker Center using the road through Quaker Center to get there. He was requested not to do so until the matter was investigated.

S. E. Cochran was thought to have cut trees on the Quaker Center property. He responded that he had cut them on his own property and had merely laid them on the Quaker Center property for a while, being in a hurry. He states he has always been on the best of terms with Lucile Manley and could not imagine she would be upset by his temporarily leaving them there. [letter of 12/20/49]

In 1958, Leon Carley of Sequoia Seminar thanked Sam Balovich for his hospitality during a work day improving the road. He agrees that Sam can use Hubbard Gulch Road to access his property, but that he must participate in the care of this shared facility.

By the end of the first decade of AFSC’s ownership of the Ben Lomond property, Camp Unalayee had left for Trinity County. Sequoia Seminar, the only remaining tenant there with the exception of Lucile Manley and Edith Cold, continued to feel strongly, as expressed in letters and notes from that decade, that it was actually the organization which was carrying out the Manley trust to see that the property “be perpetually dedicated and used for summer camps, conference grounds, and other purposes for the enjoyment, betterment, education, and welfare of mankind”. It saw no reason to imagine doing anything else for the foreseeable future. Whether Friends made any use of the property, or even visited it, during the later years of the 1950s, is not recorded.

Next section: 1960-1965 >

< Return to section : Before 1949